Factors Determining Wages

There are many situations in which one human works for another. They

range from slave to partner. The range of differences in power between

counterparts in these relations differ greatly from slave and master to

partner and partner. A third factor to consider is the size of the pool

of laborers not already employed. Records of slavery practiced against

individuals show that slavers had clear knowledge of the amount of food

necessary to maintain the lives of slaves, the amount necessary to

maintain productivity, etc. In wartime Germany and Japan, captured

soldiers, foreign nationals, and certain minorities were enslaved and

individuals were considered entirely expendable. Keeping prisoners

alive required a certain amount of food. Keeping prisoners alive and

working required more. When food was not available in the required

quantities, work would suffer and slaves might die. But the labor pool

was plentiful.

Slave holders in the United States took care to preserve their

investments. Slaves were valuable property, both because of their use

in the ardurous work of harvesting cash crops such as cotton and

tobacco, and also for their status as capital goods. Raising a slave

with a good constitution to saleable age was a good investment for the

slave masters.

After the Civil War ended in the United States, the legal status of

those who had been slaves changed. However, the economics of raising

crops requiring great numbers of workers, especially at harvest time,

had not changed. The owners of plantations needed to employ the same

number of workers, and it was in their interest to reproduce the

conditions of life under slavery as closely as possible. It was most

profitable for the plantation owners to pay the least wages that, in

combination with repressive means, could hold an adequate labor force

in their employ. In some ways the plantation owners were freer to cut

costs because, no longer owning their workers, as long as they could

maintain adequate work for numbers the fate of those who fell out of

this virtually captive work force was of no concern to them.

Sharecroppers could be exploited to the point that they could only

marginally maintain theor own health and safety. No concern need be

given to education, recreation, or other "frills."

A similar system of landlord-tenant relationships was maintained for

hundreds of years in China, and the bitter feelings that had

accumulated by the nineteenth century fueled both the revolution that

ended the Manchu Qing dynasty and the following communist revolution

that siezed control from the Nationalist party, the KMT (國民黨 Guó Mín

Dǎng or Kuo Min Tang in the old romanization system). The CCP (Chinese

Communist Party) supported much of its nation-building efforts by

acerbic attacks against the old land lord class. The KMT only began to

make real progress when, after their territory was reduced to Taiwan,

they conducted a thorough land-reform policy that ended the age of the

land lords and transformed the former land lords by giving them

incentives to invest their wealth and capabilities in capitalist

enterprises. Experiences of generation after generation of tenant

farmers indicated to everyone that there was no decent form of

paternalism at work in the vast majority of these relationships. Land

owners took as much as possible of the wealth gained by farming for

their own use. Patterns of arbitrary control that may have been worked

out in order to rule over tenant farmers and other servants were even

applied by elders to the younger generations of their own families, and

the position even of married women, concubines, and women who were

sexually available to the land owners were very similar to the

positions of complete slaves. To get a semi-autobiographical account of

life under this system, read the novel Family by Ba Jin. (See The Family translated by Wu Jingyu.)

Examine the situation of workers and employers in the world today. What

conditions place limits on the jobs that workers are willing to take,

absent any of the overt coercive factors seen in prisons and in

countries that are run like prisons? The ultimate limitation is that

ill-paid workers become too infirm to work productively (a detriment to

the employer), too infirm to work, or die. Unless there are high rates

of unemployment that might make workers stay on the job to at least

have stomachs that are partially full, unless there are no social

safety nets that provide a survival-level income to unemployed people,

then workers will not work without the prospect of being able to stay

alive at these jobs. In some cases, workers will remain homeless while

accepting part-time and/or bare-survival jobs. The only financial

reason an employer would pay more than the bare minimum would be

considerations of training new laborers after the old have departed.

Employers in industries that involve unskilled laborers and produce

products with no observable advantages over the products of their

direct competitors may be forced to pay no more than their competitors

wage rates because otherwise their products would be priced out of the

market.

Supply and demand conditions dictate that higher wages will be paid

only when the supply of workers needed for a certain class of laborers

is limited, forcing the employers to compete with each other on the

basis of compensations offered to laborers. In this matter employers

have some flexability since workers may be willing to work for lower

wages if they get health insurance, on-site daycare, or some other kind

of service that would be expensive for them but can be bought for less

by the employer because of the business's buying power. Furthermore,

any attempt by a relatively small competitor in a market to give higher

wages might be met by their counterparts deliberately lowering their

prices to force the deviant employer out of business. If corporations

are "persons," they are probably sociopaths.

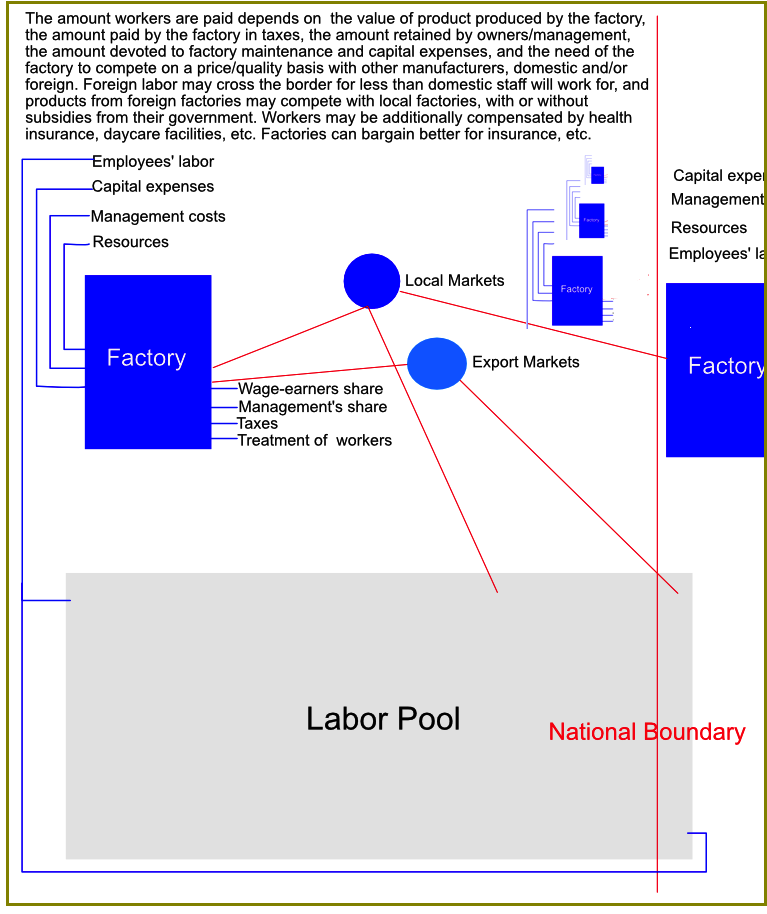

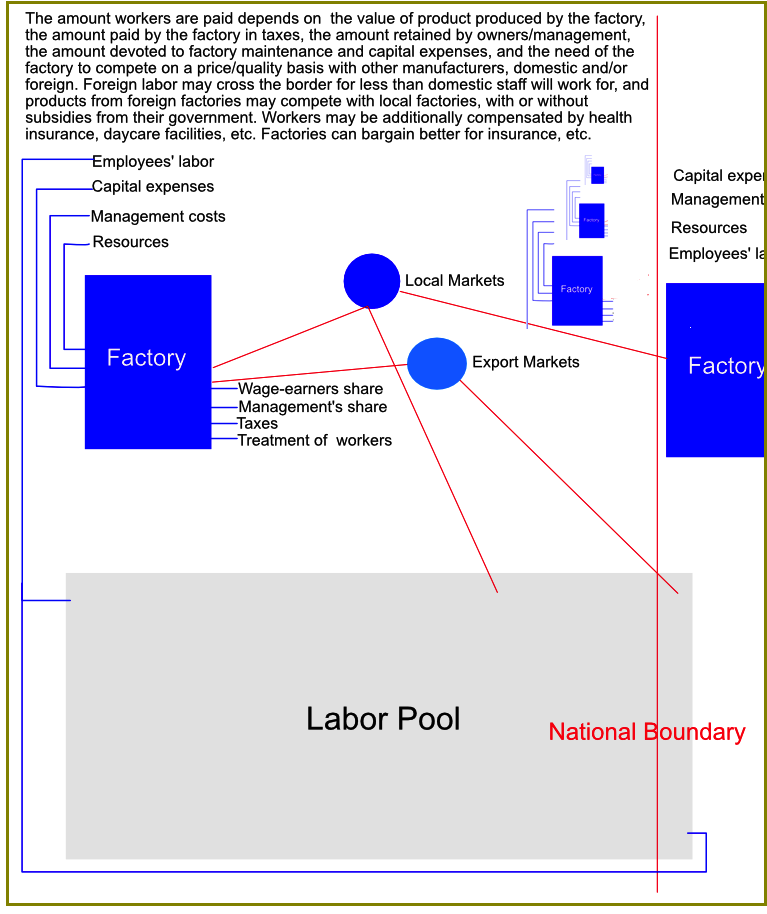

A second determinant on the dispersion of wealth gained by a factory or

other business is how much local, county, state, and federal

governments take in taxes. Typically, business owners will argue that a

raise in taxes will force them to discharge employees.

A third determinant is the share allotted to themselves by the owners,

corporate officers, etc. Certain amounts must be devoted to

maintenance, capital expenses such as essential replacement of

manufacturing equipment, etc. Typically businesses will allocate some

funds to regional charities and other such public-relations

opportunities.

Government is at least theoretically in complete control of taxation.

Neither management, labor, nor any other interested parties have any

direct way of affecting this amount, so it can be treated as a constant

so far as anything done within the scope of the financial year.

The amounts allocated to non-salary compensation to workers, e.g.,

health insurance, to wages, and to management are entirely up to

management except in the increasingly rare situations where labor

unions represent workers' interests

It has somehow come to be accepted that the only purpose of a

corporation is to make money for its shareholders. If this idea is

accepted as an axiom, then it appears that management must look for tax

loopholes so as to limit that loss to shareholders, limit non-salary

compensation to workers that cannot be justified as actually adding to

the bottom line, and limiting to the bare minimum the wages paid to

workers, keeping in mind that below some limit production will suffer.

To judge by the incredible increases in salaries and bonuses to

management over the past few decades, management will not limit its own

salaries to increase the payout to investors unless the latter organize

themselves to force management to cut back.

Within a nation such as the United States, this problematical situation

with regard to the compensation offered to workers is a variant of the

Tragedy of the Commons. When some land in England was held as the

private property of the landed classes, and some land was held in

common by all residents of an area, the only way to control

exploitation of the commons (typically as pasture) was for each

individual engaged in animal husbandry to raise more sheep or other

hebivores and therefore indirectly harvest more forage. While 20 sheep

might be scrawnier than 10 sheep raised on the same piece of land, the

total forage transformed into meat would be greater for the larger

number of animals. However, taken to an extreme, the pastures became

overwhelmed by browing and the whole system could fail. The answer had

to be to find one way or another to cap the number of grazing animals

and allocate a percentage to each husbandryman. The end result,

however, was the end of the commons. Originally, matters could have

been handled by individuals all agreeing not to over-pasture the land,

but human nature evidently never even made that a possibility that some

community tried to realize. It would only take one non-compliant

individual to ruin that scheme.

In the labor situation, one employer might have a conscience and

attempt to provide workers with higher wages. However, high owner

earnings are a function of rake-off. Employers with only a few workers

cannot ordinarily pay themselves much more than they pay their workers.

If twelve workers are paid a minimum living wage of $11,000 and they

each earn $12,000 for the company, then the owner can have $12,000 for

himself. However, if 120 workers are paid the same way and provide the

company with the same earnings, then the owner can have $120,000 for

himself. Turn this dynamic around and it is clear that an owner with

1,000 workers can do nicely with a much smaller rake-off. However, if

that owner later decides to take less for himself and distribute the

balance among employees, then that will mean that each employee is

benefitted relatively little.

A more promising approach would be for the company to charge more per

widget, and earn enough more money that it could afford to increase

worker wages. In the end it might reap benefits to itself by this

change since workers would be more contented, would work in better

health and with better morale, etc. However, the individual company

cannot do this any more than an individual husbandryman could seek to

save the commons by voluntarily reducing his own number of stock on the

pasture. The other companies would price this maverick company out of

the market, the company would fail, and the workers would become

unemployed.

It might well be that all or almost all of the heads of the various

companies in this economy would favor paying employees more money, but

they know what will happen if they move independently. It therefore is

an unavoidable consequence that government must act in pursuit of the

common good. It must enforce some level of minimum compensation for

workers, not only because it may comport with the desires and

intentions of many employers, but also because it is a social good for

all members of the society to achieve a reasonable standard of living.

When economies that can interact have not reached equilibrium, when the

wages that would support a worker adequately in one economy are far

lower than what is required in another economy, then another layer of

complexity is added. For instance, Mexican farm workers are willing to

take sub-standard wages and even work as undocumented workers subject

to all kinds of coercion from unscrupulous employers because the money

they manage to save will support their families back in Mexico in a way

their working in Mexico could not do. Manufacturers in cities bordering

on the US-Mexico border can hire laborers who work in the US but live

in Mexico. They will work for less and do work that is unappealing to

US citizens who can do better at other jobs. Manufacturers in the US

may establish entire factories in Mexico, pay workers the going rate in

that country, and sell their product to US markets. All of these things

can impact US workers who must now compete with people able to survive

on much lower salaries.

People who complain about government interference with capitalistic

principles by having government mandated minimum wage standards cannot

logically be opposed to free competition among laborers on both sides

of the border for the same jobs. China is just as capable of producing

laptop computers as is the US. Those computers will reach US markets

unless draconian import restrictions are imposed (which denies the

general advantage in wealth creation demonstrated to hold true for all

trading opportunities), and they certainly will reach other countries

where the US may be seeking to sell computers. The alternative to a

situation of anarchy in which foreign workers find it necessary to work

under sweatshop conditions and US workers lose their jobs is to

regulate international transactions to moderate the rate at which

equilibrium is reached while benefitting both e.g., Chinese workers who

need to be protected against exploitation by a new vampire capitalism

there, and US workers who need to have their jobs not migrate to China

so rapidly that their own economy does not have time to make a smooth

transition to new job opportunities.